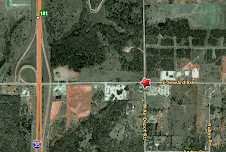

Sherwood, Missouri was situated at the present-day

intersection of JJ Highway and Fir Road in Jasper County between Joplin and

Carl Junction. Only the cemetery remains

at the end of a narrow lane off Fir Road.

Jasper County had a rich farming tradition,

agriculturally and in livestock. The

area had an abundance of vegetation and game. This prosperity and abundance led

to the destruction of the area as both northern and southern troops pillaged

the area for food for themselves and their animals and the valuable lead and

mineral resources during the Civil War.

At the time of the Civil War, Sherwood was the third

largest village in Jasper County. On May 18, 1863, Jasper County guerrilla

leader Thomas Livingston surprised and overran a foraging party of Union

soldiers near Sherwood. Eighteen soldiers were killed by the guerilla band on

May 18, 1863.

Fifteen of the dead were colored troops stationed at

Baxter Springs, Kansas. The following

day Union troops from Fort Blair came into Missouri and burned the town of Sherwood;

most of Livingston's men lived in and around the area. The citizens fled to

Texas; Sherwood was never rebuilt.

**********

Two sure things about a war – the victors of the

battle get to name it and both sides tend to succeed in marring the name of

their opponents.

Major Thomas R. Livingston is often referred to without

rank and full name making him appear as “lawless bushwhacker” to his Union

opponents, but to his friends and neighbors he was a “respected bushwhacker.”

Born in 1820 in Montgomery County, MO (about 100

miles NW of St Louis), he settled just west of Carthage MO in 1851. While

digging a cellar, he discovered lead ore and with his half-brother, William

Parkinson, he erected a smelter and entered the lead mining boom in southwest

Missouri. Both Livingston and Parkinson

would be killed during the war.

During the “bloody Kansas” era, in the 1850s,

Livingston was captain of a Border Guard unit raised to defend western Missouri

against the marauding Kansas Jayhawkers. When war came in 1861, Livingston,

then 41 years old, was a wealthy businessman and community leader. Although he

owned only one slave, he believed in fully defending the states’ rights of the

south.

The majority of the Confederacy's lead used in

armaments came from Missouri mines. As a benefit of his mining involvement, he

was elected captain in the 11th Cavalry Regiment of the Missouri State Guard.

On September 8, 1861, Livingston joined John Mathews

in a 150-man cavalry raid into Kansas in retaliation for the burning of

Missouri towns. They sacked and burned

the small town of Humboldt. Humboldt had become a refuge for abolitionists who

had tried to settle illegally on Indian land; many Indians joined the cavalry

unit.

After the Confederate defeat at Pea Ridge, March 6-8,

1862 in Benton County, AR, what remained of the Missouri State Guard was merged

into other units. Livingston, along with

many others, mustered out and came back to their homes. They found Union troops, disciplined and

undisciplined, had created nearly unlivable conditions, the men more interested

in plunder and “getting even” than restoring order; martial law was the order

of the day.

Seeing the lawlessness and disorder, Livingston

began gathering up his former troops and recruited more until he had an

organized cavalry unit. Already a captain in the Confederate Army, his unit

became known as “Livingston’s Rangers.” Confederate leaders knew they had no

hope of regaining control of Missouri without the use of guerrilla forces.

He effectively controlled most of Jasper County MO

during the war. Although most of his activities

took place centering on Jasper County and crossing over into Arkansas and

Indian Territory, patrolling along the KS-MO border often brought him into Vernon

County MO (on the western border just across from Fort Scott, KS).

Livingston and his band of Confederates and southern

sympathizers were known for committing acts of arson, murder, robbery, in the

effort to disrupt Union supply lines.

These tactics outraged Union officials and civilians and his notoriety

made him a prime target for Union troops.

Then he ventured out of his territory. On July 11th,

1863, he led his Rangers northeast to Stockton MO, in hopes of capturing

supplies from a Union garrison headquartered in the courthouse.

When they arrived, the citizens of Stockton were gathered,

listening to speeches by area political candidates. Livingston and his band,

250 men, surprised the town with their arrival. About 20 militiamen were in the

courthouse. Livingston rode at front of his men waving his carbine over his

head, urging them forward. The

guerrillas surrounded the courthouse and began firing. As the Union men tried

to shut the doors and barricade themselves inside, Livingston charged the

courthouse, 'as if to ride right through the door,' as one militiaman wrote

after the fight. Once aware of his

identity, the militiamen fired, knocking Livingston out of the saddle. Three

others fell nearby. Shocked that their leader was killed, the rangers began to

retreat. As the militiamen exited the courthouse, Livingston grabbed for his

carbine and tried to get up. Additional

shots to his body stopped him. It

appeared Livingston survived the first shot since he had been wearing a steel

breastplate.

Livingston and three other Rangers were buried in a

mass grave in the Stockton Cemetery. His death was also the death of Livingston's

Ranger Battalion. The men split up joining other units.

Before the War, Livingston had been a successful and

prominent business man. Along with his lead mine, he owned a general store,

hotel, saloon, real estate in three counties, and traded in livestock. After

the war, his assets were sought as restitution for his actions. His property

was confiscated and used in paying off the lawsuits against him for his wartime

deeds.

Three months after the Stockton incident,

Confederate Gen JO Shelby and his men burned the Stockton courthouse.

*********

Livingston's Hideout was probably the only

Confederate camp inside Kansas during the Civil War. In the corner of southeast

Cherokee County, KS, it was about 2 miles north of the border with Indian

Territory and less than 100 feet west of the border with Missouri. It was 5

miles from Baxter Springs, the site of Union military posts. The campsite was

in a heavily wooded area and could not be seen from the nearby roadway.

The location of Livingston's hideout frustrated the

area's Union troops. Many times the troops chased the guerrillas, only to have them

scatter and “vanish.” Union troops did

not know of its existence until after the war.

In the 1980s during construction of a new home, the

site was again discovered and explored by the Baxter Springs Historical

Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment