When the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi withdrew from the bloody ground on Dec 7, 1862, the Union forces claimed a strategic victory; Missouri and northwest Arkansas would remain under Federal protection.

When the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi withdrew from the bloody ground on Dec 7, 1862, the Union forces claimed a strategic victory; Missouri and northwest Arkansas would remain under Federal protection.General James Blunt’s Union command remained in the Cane Hill area after the engagement there on Nov 28. This encouraged General Thomas Hindman to attack the Federal troops with his Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi stationed at Fort Smith 30 miles away.

The Southern army crossed the Arkansas River on Dec 3rd and marched north into the Boston Mountains. Blunt, alerted to the Confederate threat, telegraphed for assistance from the 2 divisions of the Union Army of the Frontier under the command of General Francis Herron camped near Springfield, MO, about 120 miles away. Herron ordered a forced march to join Blunt’s command at Cane Hill before the Confederate attack.

The Southern army crossed the Arkansas River on Dec 3rd and marched north into the Boston Mountains. Blunt, alerted to the Confederate threat, telegraphed for assistance from the 2 divisions of the Union Army of the Frontier under the command of General Francis Herron camped near Springfield, MO, about 120 miles away. Herron ordered a forced march to join Blunt’s command at Cane Hill before the Confederate attack.At 6:00 AM, Dec 6, in the vacinity of the Cove Creek and Cane Hill roads, Gen J.O. Shelby's brigade attacked, with heavy fire, the front and both flanks of a scouting party of the Second Kansas Cavalry. Other Confederates were in position on Wire Road; the rest of Hindman's Southern forces arrived and camped near the home of John Morrow on Cove Creek Road. During the night, the Southern commanders learned that Herron’s Union troops had arrived at Fayetteville. They decided to march north past Blunt and intercept and attack the Union reinforcements somewhere between Fayetteville and Cane Hill. It would be at Prairie Grove.

The battle began at dawn on Dec 7, with the defeat of Union cavalry by Confederate mounted soldiers a mile south of the Prairie Grove church. Federal troops retreated toward Fayetteville pursued by the Confederate cavalry. The panicked Union soldiers stopped running when Herron shot a soldier from his horse.

The Confederate cavalry skirmished with Herron’s main army before falling back to the top of the Prairie Grove ridge, where the Confederate artillery and infantry were already in line of battle in the woods.

After crossing the Illinois River under artillery fire, Herron positioned his artillery to exchange fire with the Confederate cannon. The superior range and number of Union cannon soon silenced the Southern guns, allowing the Union infantry to prepare an attack on the ridge. Before the infantry advanced, the Union artillery pounded the Southern position on the ridge for about 2 hours.

The Twentieth Wisconsin and Nineteenth Iowa Infantry regiments crossed the open corn and wheat fields in the valley before surging forward up the slope, capturing the Confederate cannon of Capt William Blocher’s Arkansas Battery near the home of Archibald Borden. The Union soldiers continued their advance until suddenly the woods erupted with cannon and small-arms fire. The Confederates surrounded the Federal troops on 3 sides and quickly forced them to retreat to the Union cannon in the valley.

A Southern counter-attack went down the slope into the open valley, where it met with ammunition composed of small lead balls inside exploding projectiles. Herron’s artillery also used canister shot, consisting of tin cylinders filled with iron balls packed in sawdust which, when fired, turned a cannon into a giant shotgun blast, leaving gaping holes in the Confederate ranks and forcing a retreat to the cover of the woods on the ridge.

Seeing Confederate movement on his flank, Herron decided to attack again. The Thirty-seventh Illinois and Twenty-sixth Indiana Infantry regiments went up the hill into the Borden apple orchard. LtCol John Charles Black of the Thirty-seventh Illinois led the way with his right arm in a sling because of a wound he had sustained at Pea Ridge 9 months earlier. Outnumbered, the Federal soldiers fell back to a fence line in the valley, where they stopped another Confederate counterattack using Colt revolving rifles carried by the men of Companies A and K of the Thirty-seventh Illinois. Black sustained a serious wound to his left arm but remained with his command until it was out of danger. Black received the only Medal of Honor awarded for this battle.

Seeing Confederate movement on his flank, Herron decided to attack again. The Thirty-seventh Illinois and Twenty-sixth Indiana Infantry regiments went up the hill into the Borden apple orchard. LtCol John Charles Black of the Thirty-seventh Illinois led the way with his right arm in a sling because of a wound he had sustained at Pea Ridge 9 months earlier. Outnumbered, the Federal soldiers fell back to a fence line in the valley, where they stopped another Confederate counterattack using Colt revolving rifles carried by the men of Companies A and K of the Thirty-seventh Illinois. Black sustained a serious wound to his left arm but remained with his command until it was out of danger. Black received the only Medal of Honor awarded for this battle.With only 2 fresh infantry regiments left, Herron sensed danger as Confederate troops began massing to attack the Twentieth Iowa Infantry, on the Federal right flank. Before the attack, 2 cannon shots rang out from the northwest at about 2:30 PM, signaling the arrival of Blunt’s command; he quickly deployed and attacked the Confederate left flank. Blunt’s division was at Cane Hill the morning of Dec 7 expecting to be attacked by the Confederates. Hindman left Col James Monroe’s Arkansas cavalry on Reed’s Mountain to skirmish with Blunt’s Federal troops while the rest of the Confederate army marched past the Union position. The ruse worked, as Blunt’s command remained in a defensive position at Cane Hill until it heard the roar of battle at Prairie Grove. Marching to the battlefield, the Union soldiers under Blunt arrived in time to save Herron’s divisions.

The Confederates responded to the Union advance on their left flank by skirmishing in the woods with the Federal troops until Blunt gave the command to fall back to his cannon line in the valley. Believing this was an opportunity to win the day, Gen Mosby M. Parsons, in command of the Confederate Missouri Infantry brigade, launched an attack across the William Morton hayfield at about 4:00 PM. As the Southern soldiers advanced, a devastating fire from all 44 cannon in the Union army tore into the Confederate ranks, which fell back to the cover of the wooded ridge as darkness fell.

The Confederates responded to the Union advance on their left flank by skirmishing in the woods with the Federal troops until Blunt gave the command to fall back to his cannon line in the valley. Believing this was an opportunity to win the day, Gen Mosby M. Parsons, in command of the Confederate Missouri Infantry brigade, launched an attack across the William Morton hayfield at about 4:00 PM. As the Southern soldiers advanced, a devastating fire from all 44 cannon in the Union army tore into the Confederate ranks, which fell back to the cover of the wooded ridge as darkness fell.Nightfall ended the fighting, neither side gained an advantage. The opponents called for a truce to care for the wounded and gather the dead. During the night, the Confederates, out of ammunition and food, wrapped blankets around the wheels of their cannon to muffle the sound and quietly withdrew from the ridge. Federal troops slept on the battlefield with few tents or blankets and without campfires even though temperatures were near freezing.

Hindman’s command had 204 men killed, 872 wounded, and 407 missing with several of the missing being deserters. The Federal Army of the Frontier had 175 killed, 808 wounded, and 250 missing.

The battle was a tactical draw, with the casualties about the same in each army. But the Southern retreat during the night gave the Union a strategic victory; a full-scale Confederate army would never return to northwest Arkansas, and Missouri remained firmly under Union control. This savage battle was probably the bloodiest day in Arkansas history.

The battle was a tactical draw, with the casualties about the same in each army. But the Southern retreat during the night gave the Union a strategic victory; a full-scale Confederate army would never return to northwest Arkansas, and Missouri remained firmly under Union control. This savage battle was probably the bloodiest day in Arkansas history. |

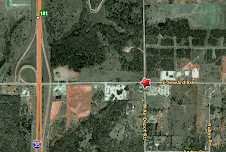

| Borden Apple Orchard |

|

Area of the corn and wheat fields |

No comments:

Post a Comment